Welcome to our second installment of Now We’re Talking!

In this post, we interview Alyson Taylor, who was diagnosed with Developmental Apraxia and shares her stories in her own blog: Girl With A Funny Accent. Alyson is a passionate and dedicated advocate in the apraxia community, and wants to help connect parents and their children through her writing and community service.

Thank you to Alyson for collaborating with us, and enjoy reading!

Q: Tell us a little about you and your adult life.

A: My name is Alyson Taylor and I was diagnosed in the mid-nineties with Developmental Apraxia of Speech. This was rather intimidating given the limited information about the disorder; there wasn’t even a Wikipedia page! Through supportive family, friends, and resources, I was able to mostly overcome Apraxia. The only reminiscent effect I have from it is an accent, but I wouldn’t change it for the world.

In my fight to overcome Apraxia, I learned the value of working hard and persevering to find success academically, professionally, and personally. I attended and graduated with my Bachelors in Political Science and Spanish from Emory University, a nationally ranked Top-20 University located in Atlanta, Georgia. Professionally, I now work at Warner Brothers Consumer Products Legal Department as a Contracts Administrator. However, I cannot forget my true passion of volunteering, advocating, and blogging about Apraxia and assisting the Apraxia community in any way possible.

Q: What was it like growing up with Apraxia?

A: Annoying, but manageable. There were days where I dreaded going to school. Especially when attendance was taken and we had to say “Here!”

I could not say it correctly and some kids would chuckle or comment on my poor pronunciation. The bullies were honestly the worst, but it got better as I got older. Actually, come High School my “accent” was cool.

My Speech Therapy was mediocre. I attended from when I was three years old to sixteen years old, when I personally decided to quit attending. Therapy was necessary, of course, and helped me find my voice. I enjoyed it as a naive child who only wanted prizes and games. However, as I got older and knew exactly why I was attending speech therapy, I was quickly annoyed with it. The last thing I wanted to do as a teenager was repeatedly hear, “You said this wrong, try it again.”

On a brighter note, growing up with Apraxia equipped me with an outstanding work ethic. When you work vigorously to simply verbally communicate, something I could not do until I was seven, you tend to put forth extra effort and energy into everything thereon after; such as, homework, studying, and even playing sports. Growing up with Apraxia truly taught me the value of working hard and accepting failure as a means to future success. Most adults are still learning this, yet I experienced it at such a young age.

Q: What inspired you to start blogging about your experiences?

A: My blogging could serve as a bridge between two isolated groups: the parents whose child was diagnosed and the children themselves.

As I started volunteering and increasing my involvement with the Apraxia community, I quickly discovered that the adults did not have the same perspective of their children diagnosed. Several parents described the scientific analyses and descriptions that professionals could provide them and their own Apraxia frustrations, but none could grasp what their child was thinking. Sadly, parents just aren’t psychic.

It was strange and quasi-frustrating the way adults spoke about such a disorder. They spoke about it with such a different, objective perspective. While inwardly, I’d think, how could they NOT understand? I grew up with the children’s perspective, not the adults. I knew their child’s frustration well because I’ve lived it. I felt that I had to do something to resolve this; to give parents their child’s perspective. Thus, I began to blog to bridge communications. Perhaps with my blog posts, parents can parallel it with their own child’s experiences.

Q: How has having Developmental Apraxia of Speech affected your adult life?

A: Fortunately, it has not impacted my professional or my academic adult life. But, it does impact my social interactions on a daily basis and not in the way you’d initially think. I love talking and usually I’m the loudest one in the room, but everyone thinks I have an accent!

I can’t go anywhere without someone asking me, “Where are you from? I hear an accent.” Even a couple days ago I had to explain to my Uber driver that I had a rare speech disorder, DAS. For the most part I’m honest in describing my Apraxia.

However, I also take the opportunity to have some fun with this. When I am not in the mood to describe my neurological speech disorder (which, let’s be honest, is not the most amusing cocktail conversation) I pretend I’m from London, Australia, or I’ll have the inquisitive person guess and just agree to whatever country they say. It definitely makes it interesting, especially when my friends need to play along with my white lies when we go out.

Q: What resources helped you the most growing up?

A: My dedicated parents, fantastic teachers, and the speech pathology program at California State University Northridge (CSUN). My parents were diligent in discovering why I couldn’t verbally communicate and when an Autism Specialist suggested we attend CSUN. We could not have found a better program.

CSUN has one of the leading Speech Pathology programs in the nation and after evaluating and diagnosing me at three years old, they enrolled me as a case study for their Speech Pathology department. CSUN had tried several techniques in order to find the best way to treat my Apraxia, while also recording it for future children diagnosed. CSUN was honestly the best resource; they gave me therapy 1-3 times a week for thirty minutes to an hour. This was more individualized time than I ever received through the public school district.

Q: Are there any new resources, or ones that you’ve just discovered that you would recommend to parents?

A: The Apraxia resources now compared to the nineties are absolutely amazing! The top 3 resources I would recommend are: CASANA, iPad communication apps, and any local support groups in your community.

CASANA, Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America, is the only non-profit exclusively dedicated to the Apraxia Disorder. They organize charity walks and are fully dedicated to researching the cause and treatments for Apraxia.

Also, the technology now, such as the iPad apps, is also extremely helpful in simply helping non-verbal children communicate with their parents. I would have loved to press a button to tell my parents that I wanted milk and cookies.

Nothing can beat interactions with others face-to-face either; I have attended and read about support groups specific to parents with children diagnosed with Apraxia. My greatest advice would be to go online, such as Facebook, and try to find these groups. Perhaps there’s even a group near where you live.

Q: Are there any, special moments from your childhood that stand out to you that you would like to share?

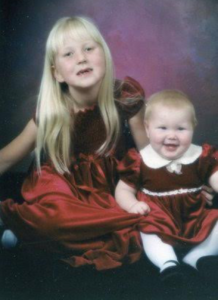

A: The two most pivotal childhood moments were the first time I met my best friend, Nicole, who treated me like a normal kid and the second was when my little sister, Sara, taught me that I actually did speak differently.

I met Nicole when I was only five years old and non-verbal at the time. She was four and she was quite the sociable girl. While I hid behind my mom’s leg, she constantly stood next to me and pulled me out of my shell. We had long play-dates and I would babble unintelligibly, but she always understood everything I said. She always treated me like I was normal, when I constantly felt different being in special-ed and speech therapy. Thankfully, we are still best friends today!

My little sister Sara also played a significant role. I was about nine years old and she was three when I was trying to teach her how to talk. It was amazing being a big sister and teaching her words. I tried to teach her to say, “Rose,” but she kept saying “Wose.” After several minutes of her merely mimicking what I was saying incorrectly, my parents corrected me aloud, “Alyson, pull back your tongue when you say ‘R.’”

I was mortified. My parents were teaching me, the big sister, how to speak at the same time my baby sister was learning to speak. That’s when I realized speech therapy wasn’t just for games and toys, they were hiding the fact that I spoke differently and needed to fix it.

Q: What advice do you have for parents raising a child with Developmental or Childhood Apraxia of Speech?

A: Remember when you hadn’t met your child yet. You would envision the future of your child- a football star, president, a doctor, a Supreme Court justice? Then after your child was born and later received an Apraxia diagnosis, those expectations and dreams vanished. The frivolous dreams seemed impossible; you only wanted your child to survive and at least speak aloud.

My advice is to raise your child as you would the one you dreamt about. If your child were “normal,” you would still sign them up for Scouts, a sports team, or a school club. Do the same for your child diagnosed with Apraxia. Do not ever lower your expectations for what your child can accomplish, because then they have permission to lower their own expectations in themselves. That’s the last thing any child needs to do, especially when they have the potential to be an amazing, successful adult.

Q: If you could go back in time, what would you tell yourself as a child?

A: The advice I’d give my child-self could not even fathom. However, I would tell myself that future success and happiness cannot be defined by anyone else, but it is grown from within.

I spent years hoping for people to define me as a “normal kid.” I wanted to desperately fit in and go a whole day without any comments about my speech. Come to find out, as a young adult, that only I can create and find my own happiness and confidence. Waiting for others to define me as “normal” would not give me true satisfaction.

My professional and academic accomplishments could only come from the work I put in. I couldn’t ask my speech pathologists, my teachers, or even my parents to make me truly happy, confident, and successful. I had to find it and create it for myself. My parents of course supported me in any opportunity that opened up, but I had to work for these doors to open and sometimes fight twice as hard to keep them open.